Building an Equitable Government: The What, the Why, and the How

On his first day in office, President Joe Biden signed an executive order that called for a “comprehensive approach to advancing equity for all, including people of color and others who have been historically underserved, marginalized, and adversely affected by persistent poverty and inequality”.

Federal agencies, guided by the Office of Management and Budget are now busy implementing the executive order which includes conducting agency-wide equity assessments and developing plans to address equity barriers. Based on Third Sector's experience providing technical assistance, training, coaching, and thought partnership to over 50 state and county-level government agencies working to improve outcomes for historically marginalized and excluded populations, we offer a framework, for how federal (as well as state and local agencies) can assess and reorient their systems to achieve improved and equitable outcomes.

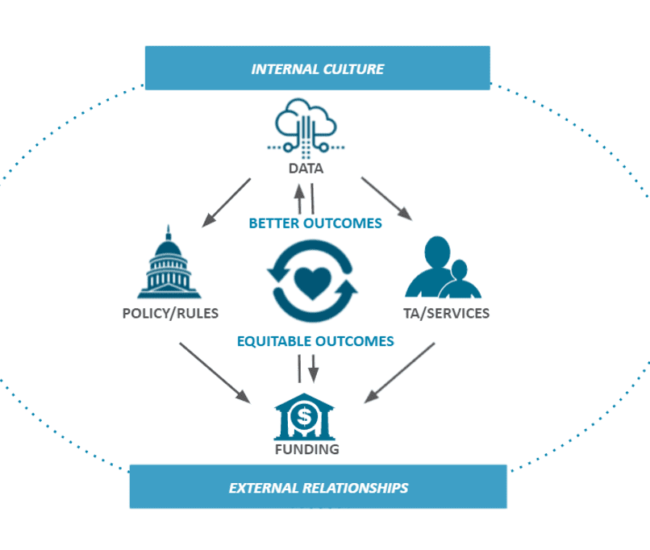

This framework involves two guiding principles and six "building blocks" that collectively determine how opportunities and benefits reach people. Achieving an equitable distribution of opportunities and benefits means embracing the principles while taking concrete action within each building block. The guiding principles include acknowledging past harm and centering end-users. The building blocks include internal culture, external relationships, data, services & technical assistance, policy, and funding.

GUIDING PRINCIPLES OF AN EQUITY-FOCUSED GOVERNMENT

Guiding Principle 1: Acknowledge the racial inequities of past policies, practices, and attitudes. To reach a state of racial equity, it is necessary to first redress the racism-rooted harms of historic policies and practices that systematically prevent Black, Indigenous, and other people of color (BIPOC) from accessing the same benefits and opportunities as white people in America. We recommend that government agencies acknowledge and center racial equity, because, while a wide variety of inequities exist in the United States, racial inequity continues to be the most pervasive and deeply embedded. In any type of inequity, BIPOC experience the impacts of discrimination most acutely. By addressing racial equity fully, federal agencies can learn how to successfully serve those experiencing the most barriers and apply those lessons to other forms of equity (gender, religion, national origin, sexual orientation, etc).

Guiding Principle 2: Equity starts by centering the end-user. At every step of an equity journey, government agencies should center and involve those who experience the consequences of the decisions of policy makers.. This includes involving diverse stakeholders in the design and implementation of equity assessments as well as the design and implementation of efforts to address barriers uncovered in the assessments. If governments do nothing else, they should find ways to meaningfully engage with those whose lives are often talked about but rarely at the table and to co-create processes and programs that meet their needs.

BUILDING BLOCKS OF AN EQUITY-FOCUSED GOVERNMENT

Changing policies, practices, and behaviors in any one of the six government building blocks will alter how day-to-day government operations are executed which, in turn, will determine the impact of the agencies' work on underserved individuals and communities. In our work with state and local government agencies, we have found that by focusing equity assessments and actions around these building blocks provides a very straightforward and usable framework that also lends itself well to developing and implementing effective solutions. Each building block interacts with the others so that inequity in any one of them means that the system overall will be inequitable. In this brief, we detail the importance of each building block, what it means for the communities and people served by public programs, and how tools, processes, and training sessions within each building block can improve racial equity.

Values, perceptions, and structures that drive people and teams’ behaviors within a government agency

What does racially equitable internal culture look like? In an agency with an equitable internal culture, staff of all races and backgrounds are comfortable being their authentic selves at work; past harms are being addressed in workplace policy and practice; BIPOC experiences and perspectives are elevated; power is shared and not dominated by white voices and it is possible for all people within the agency to raise difficult questions without fear of retribution and to test innovations without fear of failure. Furthermore, people are celebrated when they share ideas, opinions, experiences, and culture that differ from the mainstream workplace culture.

Why is this important? By doing the internal work to identify and call out systemic racism internally, agencies will have further insight into how these issues manifest and will have an easier time identifying and addressing them in policies, programs, and funding opportunities.

How do we get from racially inequitable culture to racially equitable culture? The Four Levels of Racism is a useful framework to begin understanding how racism plays out in the internal culture of an agency and to address it. These four levels are personal, intrapersonal, institutional, and structural/systemic.

- Personal: Personal racism is the private beliefs of an individual that manifest as conscious or unconscious bias towards historic attributes of power (white, male, cis-gender, straight, Christian, educated etc.)

- Interpersonal: Intrapersonal racism is how personal racism manifests in interactions between people in the form of microaggressions, interruptions, passive-aggressive remarks etc.

- Institutional: Institutional racism is racism within internal HR, staffing and work policies that results in inequitable recruitment and professional advancement outcomes for BIPOC.

- Structural/Systemic: Structural racism is the deeply embedded patterns of exclusion that cross institutions and prioritize and advantage whiteness.

Governments are likely interested in addressing systemic and institutional racism, so it may be tempting to jump directly to its institutional and structural manifestations, but these are influenced by racism at the personal and intrapersonal levels, especially within the working environments of institutions. An agency whose staff are resistant to understanding racism on a personal level will not be successful in addressing it at an intrapersonal, institutional, or systemic level.

Agencies interested in better understanding whether or not their internal culture is equitable can start by asking a few questions about the culture of their agency:

- Are differences of opinion valued in our agency? Are certain peoples’ opinions valued over others?

- How do white people in the agency feel and react when their white privilege and biases are called out? Why? Is the concept of “white fragility” understood and called out?

- How do those who are BIPOC feel about sharing thoughts and experiences they've had or seen as it relates to implicit bias, microaggressions, and other forms of racism?

- When embarking on new initiatives (internal or external), does your agency seek out diverse perspectives? Why? Why not? Who benefits and who is harmed?

- What is the recruitment and retention rate for staff who are BIPOC? For specific racial/ethnic groups? Why is it that way?

- Is it possible on your team to raise mistakes without fear of reprimand? How do unrealistic expectations of “professionalism” harm everyone, and especially BIPOC?

- Are different communications styles valued and similarly rewarded with opportunities and promotions or are certain communication styles valued over others?

To ensure an objective and safe process and to allow everyone in an agency to participate as equals, we recommend that agencies hire external consultants to work with each bureau and office on an equity review and internal culture transformation. This way, agencies will gain a shared understanding and shared language about structural racism and how it manifests in the workplace. External consultants can also help guide an agency to better understand its history of racism and past harms, address those harms, and begin working towards an inclusive internal culture.

| Case Example: At Third Sector, we have been on our own journey to build an equitable and anti-racist internal culture. This is an ongoing process, but we have taken a few concrete steps, with the support of outside consultants, towards building a more equitable internal culture and have been making progress towards that goal.

Organizational Accountability: With the help of Equity and Results, we established an organizational measurement framework that allows us to hold ourselves accountable to our anti-racist work through Better Off Measures. These measures include committing to establishing a culture where all staff members feel that their culture is celebrated, and they can bring their full selves to work. A survey of staff showed improvement on this measure from 2020-2021. We also committed to increasing the representation of people of color on our staff to 50% of all staff, at all levels, and we are rapidly approaching that goal. Of our last 10 hires, 9 are BIPOC. In the past year, we have continued this organizational commitment through work with Hella Social Impact to deepen our understanding of the actions we can take to further show up for racial justice. Team Accountability: We have consciously worked to embed equity principles into our team norms, including conversations about working styles, preferences for feedback, and how to undo white supremacist norms in our culture (e.g., perfectionism, sense of urgency). Teams establish these norms at the start of new projects and revisit them throughout the lifecycle of a project. We have also created a space for shared accountability where project teams share successes and challenges in advancing equity and troubleshoot together with fellow staff. Individual Accountability: To support Third Sector team members on their individual journeys toward contributing to a more equitable organization, Third Sector requires staff to attend Undoing Racism, a workshop offered by The People's Institute for Survival and Beyond, to better understand their individual role in either maintaining or dismantling the current disparate racial outcomes that systems and institutions produce. This work provides individuals within our organization with foundational shared language and historical understanding of racism in America so we can start or deepen our individual accountability to anti-racism. |

Infrastructure, tools, and methods that enable data collection, analysis, and data-driven decisions

What do equitable data collection, analysis, and decision-making look like? An agency that has strong equity practices with their data is being intentional about the process for collecting and using data and has involved a variety of stakeholders in creating that strategy. Data can support equity by uncovering inequities through disaggregation, demonstrating the relative success or failure of interventions for different groups, and providing background information for strategic decisions.

Why is this important? Data can be used to improve equity, maintain the status quo, or increase inequity. Agencies that do not ask questions that get to the root of inequities in the processes of data collection and analysis and use these questions to understand how they collect, analyze and use data to drive strategy, investment, and implementation decisions will likely perpetuate inequality.

How do we go from inequitable systems for data to a racially equitable system of using data? To address racial inequality through data, governments should start with three key questions:

- Do we have the data we need to talk about equity?

- How are we collecting and using that data?

- How can we use data to address equity related problems?

1. Do we have the data we need to talk about equity?

Governments need data to understand inequities in outcomes for the goals of their agency. Without high-quality data that can be disaggregated by race, income, gender, etc. agencies will not be aware of potential inequities. With that data, agencies then have a tool to understand how they are doing in addressing those inequities.

2. How are we collecting and using that data?

When agencies have access to the data they need or are in the process of determining how to collect that data, they should examine the equity implications of how they are collecting and using data and be intentional about doing so in an equitable way.

Tools that support equitable ways of collecting data include:

- Data Biographies: A Data Biography tells the story of who is collecting the data, who owns the data, how was it collected, how big was the sample, who was included or excluded by the sampling, when was it collected/updated, why was it collected, and what else is known about the data. This tool can help ensure that data is not being used to mask or perpetuate inequities. We All Count has developed two data biography tools, the simple excel template and a more comprehensive online tool (this is currently in its beta version).

- Participatory Data: Governments should also be intentional about involving community experts, states, contractors, grantees, and individuals in determining what data is collected and how it will be used. Data collection is an extractive process where the power is in the hands of those collecting the data. By involving more people and institutions in conversations about how their data is collected and used, agencies can craft a more equitable process and also improve the quality of the data they are collecting.

- Public Tools for Data Visualization: To benefit from different interpretations of data and new, crowdsourced ideas for improvement, agencies should take advantage of open data and public tools for data visualization. These tools make it easier for the public to understand data, find correlations between variables, and identify disparities in services and outcomes. When these tools are made available they need to be well advertised to the community and should be accompanied by simple data literacy courses and connections to public computer labs or libraries. Tableau’s Government Analytics is an example of a tool that can strengthen the ability of the public to draw insights from data and contribute to the conversation.

3. How can we use data to address equity-related problems?

Data is not just useful for identifying inequities in outcomes, it can also be actively used to address equity challenges. One way to do this is to consider what data might be able to be linked to provide more robust information about particular geography, program, or demographic. For example, how can more agencies at federal and state-level access and use each other's data to better understand outcomes for different populations and begin addressing inequities that this data uncovers? In the past, we have seen the Social Vulnerability Index, HUD Location and Affordability Index, WIOA performance measures, and other indices being successfully used on a case-by-case basis, but there is significant room for additional coordination and expansion of the use of these data sets.

Case Example: Participatory Data with the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe

Data on Native American communities has historically been of poor quality, inaccurate, inconsistent, and inaccessible. Efforts by tribes to find new ways of collecting and analyzing data provide a useful example of both why data is important and how access to data can support equitable programs and policies. In recent years, American Indian tribes have partnered with universities and research institutions to create more participatory data, research, and evaluation practices. For example, When the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribal Ventures program in South Dakota sought to evaluate the results of their Poverty Reduction plan, they found that the socio-economic data that showed 88 percent unemployment, was inaccurate and insufficient. In partnership with Colorado State University, they demonstrated that federal unemployment data was not able to capture the extensive informal traditional arts and crafts sector in which many tribal members were working. Through the Voices research project, they were able to identify that 78 percent of survey respondents were participating in arts and crafts micro-enterprises. Using this data, the Northwest Area Foundation was able to help the tribe’s community development fund establish a micro-loan program for small arts businesses along with other targeted economic initiatives.

Ways of interacting, power dynamics, and the level of trust between the government agency, its service providers, and community members

What do equitable external relationships look like? An agency that has strong, equitable external relationships will have clear structures that allow for collaboration with and accountability to states and local communities. They will be engaged in ongoing work to build and maintain trust. The agency will have an understanding of past harms and will be working with states and communities to address those harms.

Why is this important? Positive external relationships allow for the development of policies and programs that work for more people. Relationships with those who have been most impacted by racist policies and policies that profess equality, but reinforce the status quo, support the creation of policies that will result in greater success for those populations.

How do agencies go from inequitable external relationships to equitable relationships? To foster more equitable external relationships, agencies will need to assess historical harms, understand their own biases towards different stakeholders, and harness community expertise.

- Acknowledge how past policies and practices have eroded trust with BIPOC: By intentionally investigating and acknowledging the history and past harms done to communities and taking an honest account of the effort, or lack of effort, to address these harms, agencies can create a stronger foundation in partnership with BIPOC to address equity moving forward. Tools agencies might consider as part of this investigation of the past include a Root Cause Analysis Framework or an Upstream-Downstream Analysis to understand the implications of various policies and funding decisions.

- Addressing internal bias: Everyone holds conscious and unconscious biases that will affect how they engage with other people. To meaningfully engage with stakeholders, agency staff should develop an honest awareness of their own biases. Key reflection questions in this process may include:

- What are my assumptions or beliefs about community members' needs, solutions, or behaviors?

- Who benefits from the assumptions I have learned? Who gets harmed by the assumptions I have learned?

- How will I disrupt my own biases?

- Harnessing Community Expertise is a really important step in strengthening external relationships to build a more equitable agency. In order to build external relationships that are both equitable themselves and serve to help agencies become more equitable overall, agencies need to engage the right people, set those people up for success, and find ways to co-create and share power.

- Create a Stakeholder Engagement Plan: For the engagement to be meaningful, stakeholders need to be engaged from the beginning, even in the process of determining what the stakeholder engagement plan should be and who else should be engaged. Building on advisory groups and committees, governments can engage more people in conversations about who should be engaged and how.

- Useful Stakeholder engagement tools:

- Stakeholder Engagement Map (see p. 37-38 in the Workplace Ecosystem Mapping Guide)

- Stakeholder engagement continuum

- Useful Stakeholder engagement tools:

- Create a Stakeholder Engagement Plan: For the engagement to be meaningful, stakeholders need to be engaged from the beginning, even in the process of determining what the stakeholder engagement plan should be and who else should be engaged. Building on advisory groups and committees, governments can engage more people in conversations about who should be engaged and how.

- Be explicit and intentional about representation: In order to anticipate the effects of policies on various communities and groups, an agency may intentionally recruit and expect community experts to represent a specific demographic group.

- Set people up for success: When engaging new people, many of them will not have experience in this type of engagement and current processes are often not designed for them. Agencies serious about engagement will need to provide a variety of supports to ensure people are set up for success. Designated time and resources are necessary to devote to making materials accessible, reducing burdens for participating (compensation), and skilled facilitation of diverse groups.

- Find ways to co-create and share power: Actively engaging stakeholders in a meaningful way means offering them more than the opportunity to provide input upfront. It means opening up decision-making processes and creating clear pathways for sharing power.

- Value and pay for community expertise Community experts should be valued and should be paid in the same way that other subject-matter experts are paid. Compensation should recognize the time, travel, expertise, and emotional investment that it will take for community experts to share their perspectives. Compensation should be determined in partnership with community experts to ensure unintended consequences of compensation are considered such as any impact on benefits eligibility.

The contracting systems that deploy public funds into communities in alignment with policies

The entire system around grantmaking and contracting is covered by this building block. It concerns the question of HOW taxpayer funds are deployed in communities in alignment with government priorities.

What does equitable funding look like? A system of equitable funding makes a clear link between funding decisions and increasing equitable outcomes. Equitable funding and contracting opportunities need to address historical oppression and discrimination and provide meaningful correction to those policies of oppression and discrimination. Additionally, an equitable funding system should have pathways for smaller organizations and contractors to be successful in accessing government funds.

Why is this important? Government funding sources have real potential to positively impact historically disadvantaged communities. They also have the potential to exacerbate historical inequality if deployed unfairly. Whether amounts included in entitlement programs, a funding formula in a block grant, or the process for procuring and selecting winners in a discretionary grant competition, policies and practices involved in each funding mechanism dictates how the "money will meet the people" and how equitable the outcomes of the funding will be.

How do agencies go from inequitable funding to equitable funding? Government agencies need to carefully examine their funding and contracting policies and practices and become more intentional about making opportunities equitable. For entitlement and blockgrant funds, agencies should review and strive to revise amounts and allocation formulas and rules to drive resources to communities based on actual need and to correct for past inequities. For discretionary grant funds, agencies should review and revise how programs get designed and how grantees get selected and supported to ensure that funding for publicly funded services is consistently used to advance equitable outcomes.

- Review and streamline “allowable expenses”. Agencies should review how their interpretations and guidance on allowable expenses may perpetuate inequities. For example, the Environmental Protection Agency has explicitly clarified that compensating community members for participation in focus groups and other stakeholder engagement exercises is an allowable expense while the Department of Agriculture questioned it in a recent grant application.

- Ensure that auditors and financial monitors are engaged and supportive. Efforts to use funds to meet actual needs by blending and braiding funds, emptying outcomes-based contracts, or deviating from original budgets to provide supplemental services are often met with resistance from federal auditors and monitors. To encourage and enable state, local and independent grantees to flexibly use funds in ways that maximize equity and impact, agencies should review and revise auditing policies and practices to be more supportive rather than punitive. By including its auditors and monitors in equity conversations and developing a culture of working towards "yes" rather than looking for reasons for "no" agencies can alleviate the fear that many state, local, and independent grantees have towards federal auditors which would also increase their ability and willingness to innovate and adapt.

- Carefully review funding allocation formulas: States have the discretion to set entitlement fund levels and allocate and appropriate many blockgrant funds as they see fit. This is an opportunity to take measurable steps towards equity-promoting entitlement levels.

- Review and revise requirements. Many government grants and contracts require a huge amount of administrative work that can be prohibitive for smaller agencies and organizations. Despite having fantastic solutions to offer communities, smaller entities may not have the resources or expertise to prepare competitive proposals or meet stringent evaluation and reporting requirements. To begin reviewing the administrative requirements in competitive procurement processes, agencies can ask themselves four questions about application and reporting requirements:

- Why do we have each requirement?

- What is the impact of each requirement?

- Who is advantaged or disadvantaged by each requirement?

- If requirements are disadvantageous to specific groups of people, for example, BIPOC-led organizations, what support could be offered to even the playing field?

- Promote inclusive and cooperative procurement: Invest in greater transparency and simplicity to broaden opportunities for small businesses. Consider promotion of inclusive and cooperative procurement arrangements so minority-owned businesses go through minimal certification procedures to contract with multiple government agencies.

- Ensure that a diverse group of people is selecting awardees: By engaging a diverse pool of individuals in selecting awardees, agencies can reduce implicit bias. When selecting people to participate in these processes, agencies should consider diversity across as many factors as possible including race, education, income level, gender, lived experience, and more.

- Ensure that solicitations issued for discretionary grants and contracts reflect the focus on equity. With input from diverse stakeholders (see external relations above), goals, objectives, and the scope of work in competitive fund solicitations should make advancing equity an explicit aspect of the work. Equity should also be advanced in other areas of the solicitation. For example, the key personnel section can make lived experience with a particular program a desired area of expertise, the past performance/corporate capability section can value community engagement experience equal to federal contracting experience, and the budget narrative can call out equity-enhancing activities as its own category.

| Case Example 1: Creative funding allocation to advance equity for childcare in Connecticut

With support from Third Sector, the Connecticut Office of Early Childhood used the Center for Disease Control’s Social Vulnerability Index (SVI) to allocate childcare stabilization funds from federal COVID relief based on centers’ location and abilities to serve children from low-income communities. By setting allocation amounts in proportion to higher scores on the SVI, more minority-owned childcare providers and more providers serving low-income and BIPOC communities were able to qualify for greater award amounts to match their proportionally higher needs. Case Example 2: Equity centered in a workforce solicitation in Washington state A recent solicitation from a workforce board in Washington state took exceptional care to center and elevate equity when procuring for a WIOA youth service provider. In the scope of work, the solicitation asked bidders to “describe outreach, service strategies, and partnerships that will engage all or many high priority populations, and/or strategies and partnerships tailored to specific populations”. The solicitation also explicitly asked for proposals from "organizations whose board of directors, leadership, and staff reflect the communities prioritized for services in this RFP". Finally, the solicitation clarified that the board “does not require bidders to have a comprehensive understanding of WIOA requirements and processes”. and that the board would "provide technical assistance and training regarding WIOA requirements to sub-recipients chosen through this solicitation". |

The activities delivered by organizations to improve life outcomes of certain populations within a community or the training and technical assistance to support service implementation

What does it look like to improve equity in services, training, and technical assistance? Agencies have an opportunity to assess equity within their own services while also providing tools and technical assistance to grantees to do the same.

Why is this important? Grantees, especially State and local government agencies may not have the resources, knowledge, or political will to build their own organizational capacity with respect to equity. Embedding a racial equity lens into all training and technical assistance offered by agencies and making this assistance easily available to grantees improves the likelihood that equity principles are consistently applied at the local level in a way that benefits people serviced by public programs.

How do agencies go from inequitable services and TA to equitable services and TA? Whether services and TA are being provided by agency staff or by contractors, agencies should ensure that services and TA reflect the focus on equity. For services, this means that enrollment, engagement, and follow-up are equitably designed and implemented. For TA, this means that TA providers are well-versed and able to apply equity principles, that TA scopes make equity an explicit area of focus, and that TA providers are held accountable for equity-related results.

For Services:

- Use an accountability framework: A conceptual accountability framework can help agencies analyze available data to critically assess how well a particular service or program is achieving its intended impact. One such framework that has an explicit focus on equity is Clear Impact’s Results-Based Accountability framework which uses a data-driven, decision-making process to help organizations understand and take actions to improve services for a specific client population. RBA asks three key questions: How much did we do? How well did we do it? and Is anyone better off? It then presents clear steps for how organizations can employ "turn the curve thinking" to get from their current state to the desired end state.

- Equity Centered Evidence-Based Practices Apply a critical equity lens to the use of evidence-based practices. Using evidence-based practices helps ensure that services will have the desired outcome by following models proven by rigorous evaluation. While a strong evidence base supports positive outcomes for participants, governments should also ensure that they have applied an equity lens to any evidence-based practices they have adopted. Programs that are strong in overall outcomes may have weaknesses with certain groups and requirements for using evidence-based practices may hinder the use of interventions that have success with specific priority populations but have not undergone a randomized control trial.

For TA:

- Make equity advancement a key consideration and component of all TA contracts. agencies should acknowledge and harness the power and potential of implementation and evaluation TA to help services achieve equitable impact. Current TA is primarily focused on helping grantees meet compliance requirements, adopt an evidence-based service approach, or participate in evidence-building activities such as random control trials. While this TA is important, it does not inherently advance equity. To ensure that equity is diffused to state and local levels, agencies should embed equity advancement as a required skill and component in TA grants and contracts.

- Streamline the use of outcomes-focused TA (OFTA): Because grantees may not have the resources, capacity, or political will to embrace and operationalize equity in data, funding, and services, federal agencies should make OFTA readily available to all grantees. OFTA is TA that explicitly focuses on helping diverse stakeholders come together to collectively design, implement and continuously improve services and the administrative systems behind those services. At its core, OFTA is a facilitated system change process that helps clients establish clear impact goals and objectives and then use data, stakeholder engagement, and continuous improvement to reorient policies, programs, and behaviors in support of those goals.

| Case Example: OFTA improves equitable services for people experiencing serious mental illness in California

In California, a cohort of six counties is working with Third Sector Capital Partners as an OFTA provider to help them streamline and improve programs serving people experiencing serious mental illness. With the support of OFTA, the counties are implementing a more uniform data-driven approach to care by streamlining definitions, metrics of success, service requirements, graduation guidelines, and priority populations. OFTA is also helping the counties strengthen stakeholder engagement strategies and use stakeholder feedback in program redesign. By collectively engaging Third Sector as an OFTA provider, each of the counties is receiving support to establish goals and implement system change in their own counties while harnessing lessons and insights from the other counties. |

Decisions that define public sector social service priorities and funding through legislation, regulations, and official guidance

Policy is a broad building block that encompasses legislation, rules and regulations, and guidance. Agencies need to consider the language in their existing policies and how and why they came to be, the practices around creating new policy or changing old policy, and how policies are enforced.

What does equitable policy look like? Equitable policies push us closer to that vision of a society that embodies the fair, just, and impartial treatment of all individuals. But in order to get there, we need to examine and correct the current policy landscape which, due to a focus on equality rather than equity, perpetuates disparities that BIPOC experience. To improve equity, future policies must therefore explicitly prioritize and support the advancement of BIPOC who have been historically marginalized, excluded, and oppressed.

Why is this important? Rules and guidance provided by agencies to other agencies, to service providers, or to the public often reinforce inequities so efforts to improve the lives of BIPOC are constantly fighting against policies that make it harder to succeed. Policies that acknowledge the disparate outcomes for BIPOC and address them make it possible to move towards the desired state of full racial equity.

How do we go from inequitable policy to equitable policies? To achieve equitable policies, agencies need to expand opportunities for diverse stakeholders to contribute to policy development and design, and take intentional steps to review and revise past, current, and future policies to uncover and address past inequities.

- Expand opportunities for diverse stakeholders to contribute to policy development and design An examination of policy needs to start with an examination of who is at the table when the policy is developed. Why are they there? Who is not at the table and why are they not there? The best way to make policies equitable is to ensure that community experts and those with lived experience using social services have a real voice in their development. By actively working with community experts throughout the policy development process, agencies will not only gain a deeper understanding of the barriers that community experts face when engaging with various programs and funding streams but also capture the possible solutions and insights that community experts can bring to the policy itself.

- Assess and analyze past, current, and future policies with respect to equitable impact: There are several tools that can help agencies improve how policy is developed in order to improve rather than impede equity. A few of these include a root cause analysis, the Race Forward Racial Equity Impact Assessment (REIA), and the Diversity Data Kids Policy Equity Assessment (PEA).

- Root Cause Analysis will allow agencies to understand why disparities in a given program or funding stream exist and how the presence or absence of a policy can perpetuate or alleviate inequities. The most basic Root Cause Analysis tool is the 5 Whys Tool, developed by Toyota production architect Taiichi Ohno, which asks a group to select a data trend and then explore at least 5 levels of the question “why.” This tool helps uncover systemic inequities that are at the root of negative data trends, rather than placing blame on individual behaviors and circumstances. Completing the root cause analysis together with community experts will help agencies gain a deeper understanding of the impact of past and current policies.

- Racial Equity Impact Assessment: The REIA is a tool designed to examine how different racial and ethnic groups will likely be affected by an agency’s decision or action. The questions are designed to support agencies in identifying unintended consequences of policies, programs, or funding decisions. This tool can be used to prevent the reinforcement of institutional racism and to identify opportunities to address long-standing inequities.

- Policy Equity Assessment: The PEA is a tool that is designed not just to flag inequities, but to actively reduce racial inequities and gaps. This assessment has 3 stages:

- Logic: Does the policy set explicit/implicit goals to address racial/ethnic gaps?

- Capacity: Does the policy have the capacity to meet the needs of the overall eligible population and those of each racial/ethnic subgroup?

- Research evidence: Is the policy effective for racial/ethnic subgroups, and does it reduce inequities?

| Case Example: Understanding Inequitable Policy Impacts

In recent years, several states have attempted to establish work requirements for Medicaid enrollees. In “The Racist Roots of Work Requirements,” Elisa Minoff describes how these types of requirements have a disproportionate racial impact. For example, the Michigan Legislature introduced a work requirement for its Medicaid program that would have varied depending on the county in which a person lived. Those living in counties with high unemployment were exempt from the requirement, which may seem fair on the surface, but in practice, this would have meant that individuals in largely-White rural counties would have been exempt, while many Black people living in majority-Black cities in Michigan, such as Detroit and Flint, would not have been exempt from the policy despite their high unemployment because they sit in counties where the unemployment is relatively low. Though this law was ultimately struck down for violating the Affordable Care Act, an examination of the policy through an equity assessment would have revealed these challenges and encouraged the identification of alternative solutions to achieve the aim of the policy. |

About Third Sector

Third Sector is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization that is transforming the way communities connect people with human services. We help governments, service providers, and their partners use public funding to generate positive, measurable outcomes for the people they serve. We work alongside communities to help build a future that includes stable employment and housing, increased income, stronger families, and physical and mental health. When our work is complete, agencies entrusted to use public funds will have the systems, tools, and data to do more and do better for their communities. Since 2011, we have worked with more than 50 communities and transitioned over $1.2billion in public funding to social programs that measurably improve lives. Our team of more than 50 employees works nationwide and is united by our mission to transform public systems to advance improved and equitable outcomes.